St. Louis Neighborhoods

Benton Park/Cherokee Street

The Benton Park neighborhood and surrounding areas were originally part of the St. Louis Commons, a large common pasture south of the city. In the 1850s, German immigrants were pouring into St. Louis, and downtown and Soulard began to fill up. As a result, a number of Germans bought land in the commons, and began to build small homes in what was then a rural area. As a result of the new development, City Cemetery, which was founded in 1842, was converted into Benton Park in 1866, after the bodies were moved to Bellefontaine Cemetery. In the 1880s and 1890s, the area transformed into a densely populated urban area as the streetcar lines helped to create business districts along Gravois Road, Jefferson Ave, and Cherokee Street. The area continued to thrive into the mid 20th century, when suburban flight and redlining began to depopulate the area. However, the area has seen major revitalization efforts in recent years, with Cherokee Street re-emerging as a vibrant business district, and with the completion of a number of restoration projects in the surrounding neighborhoods.

Carondelet

Carondelet was founded as its own city in 1767 by Clement Delor De Treget, near the confluence of the River Des Peres and the Mississippi. In 1832, the city was incorporated, and it began to grow in size around this time, as German immigrants began to arrive in Missouri. During the 1830s-1850s, German stone masons known as Steins built a number of stone houses throughout the area, many of which are still standing today. In the 1850s, a number of Irish immigrants came to Carondelet and settled in an area known as the Patch, and worked in the industries that existed along the riverfront. The shipyards in the area played an important role during the Civil War, as James B. Eads built ironclad ships for the Union Navy here. In 1870, Carondelet was annexed by the city of St. Louis, who was rapidly expanding at the time. In 1873, the Des Peres School in Carondelet became the first kindergarten in the United States. The area continued to thrive as St. Louis grew in the late 19th and early 20th century, but in the late 20th century, it began to experience decline as industry began to dry up. However, due to the age and historic significance of many structures in the neighborhood, many have been preserved and restored.

Central West End

The Central West End was initially settled in the late 1880s and early 1890s as wealthy St. Louis residents moved west towards Forest Park to escape the crowded neighborhoods closer to downtown. Many of the wealthy private places were laid out in the neighborhood around this time, including Portland Place, Westminster Place, Kingsbury Place, and Washington Terrace. By the time of the 1904 World’s Fair, this was the wealthiest part of St. Louis. In the early 20th century, a business district was established along Euclid Ave, and in the 1920s, a number of luxury hotels and apartments, such as the Chase and the Park Plaza were constructed. In the mid 20th century, the neighborhood began to decline in certain areas as wealthy people began to move west into St. Louis County, and many mansions became rooming houses as a result. By the 1970s and 1980s, people had started to reinvest in the area, and restore many of the mansions. As a result, the neighborhood has rebounded, and is once again among the wealthiest parts of St. Louis, and features many of the largest and most expensive houses in the city.

Downtown

Downtown St. Louis is where the city was originally founded in 1764 by Pierre Laclede and Auguste Chouteau. Architecture from every decade since 1830 is represented here, including row houses and mansions from the 1840s and 1850s, commercial buildings and warehouses from the late 19th and early 20th century, as well as a number of Art Deco and Mid Century Modern Buildings. Some of the most historically significant moments in St. Louis history happened downtown, such as the beginning of the Lewis and Clark expedition and the Dred Scott trials

Hyde Park

Hyde Park was originally founded as the town of Bremen in 1844 by Emil Mallinckrodt, George Buchanan, N.N. Destrehan, and E.C. Anglerodt. The town was named after the city in Germany where most of the residents came from originally, and the main streets through the city were Broadway and Salisbury Streets. Another early resident of the area was Bernard G. Farrar, who lost his life during the 1849 cholera epidemic while saving the lives of other victims. Farrar had also donated the land at 14th and Mallinckrodt for the Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church in 1848. In 1850, Bremen was officially incorporated, and in 1854, the city of St. Louis purchased a plot of land in the city for use as a park, in anticipation of the large annexation that would take place in the following year. This plot became Hyde Park, which is the 4th oldest park in St. Louis. On July 4th, 1863, Hyde Park was the site of a riot when Civil War soldiers and neighborhood residents got into a fight at a local bar that had run out of beer. In 1871, Irving School was built in the neighborhood, and today it is one of the oldest surviving school buildings in the city. While much of the neighborhood was populated by 1870, the 1880s and 1890s saw the filling in of some of the low density areas in the northern part of the neighborhood. In the early 20th century, Hyde Park was a mixed income neighborhood with many businesses, such as Krey’s Meat Packing Co. and Mallinckrodt Chemical Company. After World War II, the neighborhood began to decline as redlining, white flight, and the construction of highway 70, which cut the neighborhood off from the riverfront. After years of decline, and an unsuccessful revitalization effort in the 1980s, restoration efforts in Hyde Park are finally starting to take off. Despite years of abandonment and disinvestment, many of the historic buildings in Hyde Park survive today.

Lafayette Square

Lafayette Park was first laid out in 1836 after the city of St. Louis began to develop land in the Commons, which had formerly been a common pasture set up during the French Colonial period of the city’s history. This makes it the oldest park west of the Mississippi. However, due to the panic of 1837, there was very little development in the area until the 1850s, after the park was formally dedicated in 1851. Lafayette Square had begun its development into a wealthy neighborhood beginning in the late 1850s and early 1860s, and in 1863, a law was passed prohibiting industrial developments from being built within 800 feet of the park, to ensure it would become a wealthy residential neighborhood. In 1868, Lafayette Square saw a lot of development, with the landscaping of Lafayette Park by Maximilian G. Kern, as well as the construction of a wrought iron fence, statues of George Washington and Thomas Hart Benton, and a police station in the park, all of which still stand. Benton Place, one of the oldest surviving private streets in America, was also laid out by Julius Pitzman in the same year. Lafayette Square continued to grow into a wealthy urban neighborhood throughout the late 19th century, but it was severely damaged by the 1896 tornado, which destroyed a number of mansions and damaged many more. Most were either repaired or replaced, but the neighborhood had begun to lose its prominence by the early 20th century, and during the Great Depression, many of the mansions were converted to rooming houses. The area had fallen into severe disrepair by the 1960s, when Highway 44 was built at the southern edge of the neighborhood, and it had been labeled as a slum on a number of urban renewal proposals. Perhaps the greatest threat to the neighborhood was the proposed construction of highway 755, which would have cleared a large area in the eastern part of the square, and would have leveled hundreds of historic buildings. However, preservationists successfully fought the plan, and had Lafayette Square listed as a National Register Historic District. Since that time, almost all of the structures in Lafayette Square have been restored, and the neighborhood has become a wealthy neighborhood once again.

Midtown

Midtown was originally developed as a wealthy residential neighborhood in the 1860s and 1870s. Many of the most prominent St. Louisans lived here, and in 1870, Vandeventer Place was laid out by Julius Pitzman, becoming the wealthiest part of the city at the time. Meanwhile, the southern part of the neighborhood, known as the Mill Creek Valley, became home for immigrants and African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th century. By the 1920s, the urban and industrial expansion of downtown began to move into midtown, and a lot of the mansions were replaced by high rise buildings and theaters. During this period, Midtown was transitioned into a bustling theater and arts district. However, urban renewal in the mid 20th century was especially unkind to the Mill Creek Valley, and dozens of blocks of historic buildings were cleared entirely from the area. The theaters had also suffered during this period, but beginning in the 1980s, and continuing today, many of the theaters have been either reopened as Broadway musical style theaters, or have been repurposed for other uses, such as hotels.

Old North St. Louis

Old North St. Louis was originally founded in 1816 by William K. Christy, Thomas Wright, and William Chambers as the village of North St. Louis. In the original layout of the town, there were three circular plots of land, one for a church, one for a park, and one for a school. These circular plots of land are still existent in the neighborhood today. As the city of St. Louis expanded in size in the mid 19th century, it annexed North St. Louis in 1841. Shortly after, the population of the neighborhood of the neighborhood rapidly expanded, as Irish and German immigrants poured into St. Louis. By 1857, Old North had the most densely populated city blocks in the entire city located in the neighborhood, as a result of this rapid expansion. Due to the number of buildings in the area from this time period, Old North has the most buildings built with limestone window lintels of any neighborhood in the city. In 1867, the Mullanphy Emigrant Homo was constructed at the southern edge of the neighborhood, and provided immigrants with a place to stay upon their arrival in St. Louis, while they established themselves. In 1875, Marx Hardware was founded, and they still operate within the original family today, making them one of the oldest family owned businesses in the city. In the 1880s and 1890s, the northern addition to the neighborhood, which had been a medium density area in the 1860s and 1870s, was filled in with a number of Second Empire mansions and multi family buildings. Old North continued to thrive into the early 20th century, with a number of businesses locating themselves on North 14th Street, with the most notable being Crown Candy, which opened in 1913. In the 1950s-1990s, the neighborhood experienced a decline as a result of the construction of highway 70, which cut the neighborhood off from the riverfront, as well as redlining and white flight, which resulted in the disinvestment in the area. In 1979, a pedestrian mall was created on 14th Street, which had the unintended consequence of reducing the number of visitors to businesses as a result of the street closure. In the early 2000s, the area saw a massive revitalization, with dozens of historic buildings being restored, and infill housing taking the place of vacant lots. Today, Old North has seen a reversal of its decline in many areas, including the reopening and restoration of 14th Street, although there are still a number of buildings within the neighborhood that are awaiting restoration.

Soulard

Soulard is one of the oldest residential neighborhoods in St. Louis outside of downtown. It gets its name from Antoine and Julia Cerre Soulard, who owned a farm in the area. Antoine Soulard was the surveyor general for the Louisiana Territory, and he had fled to St. Louis in 1795 to escape the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. He married Julia Cerre, the daughter of prominent landowner, Gabriel Cerre, and they lived on their farm, which was between Park Ave and Geyer Ave, and extended from the river out to 14th Street. Antoine Soulard died in 1825, and following his death, Julia Soulard struggled to gain control of the land, as the American laws that had replaced the earlier French and Spanish land grant laws forbade women from owning property, and as a result, Soulard fought in legal battles for the next decade in order to gain control of the land. She finally came out victorious in 1836, and became the first female real estate developer west of the Mississippi. In 1840, she had a Federal style mansion constructed at Decatur and Marion Streets, today’s south 9th and Marion. In 1843, land was set aside for the Soulard Market, which is the oldest continuously operating farmers market in St. Louis. The current building was constructed in 1927 and designed by Albert Osburg. The St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church was built at Decatur(South 9th) and Park Ave on land donated to the Vincentians by Julia Soulard in 1843. The church was completed on November 10, 1845, and is the city’s fourth oldest Catholic Church. It was designed by Merriwether Lewis Clark and George I. Barnett, with the spire being completed in 1849 by Franz Saler. Following the death of Julia Soulard in 1845, her son Henry G. Soulard continued to develop the land in the area. His mansion stood at the southwest corner of 12th and Lafayette Ave.

Soulard was one of the neighborhoods that greatly expanded as German immigrants settled in the city of St. Louis. Many German immigrants began to build their homes in Soulard in the 1840s, and this was accelerated after the failed revolutions in 1848 in the German states, as many more Germans began to come to St. Louis in its wake. By 1860, St. Louis had grown to 160,000 people, a tenfold increase from 1840, and the influx of Germans into neighborhoods like Soulard played a major role in that growth. The German population influx also resulted in the Soulard Market riots in 1852, when members of the know nothing party marched to the market with 1500 men in an attempt to stop the Germans from voting in what was then the first ward. Despite this, the Soulard neighborhood remained as a significant center for German immigrants throughout the 19th and early 20th century.

In the 1850s, the Soulard neighborhood saw an influx of residents who immigrated from central and Eastern Europe. In 1854, the first Czech Catholic Church in America was founded in the neighborhood, St. John Nepomuk Church. It grew so rapidly that in 1870, a new church building was constructed by architect Adolphus Druiding. Many of the immigrants lived in an area known as Bohemian Hill, which was mostly located near the present day intersection of highway 44 and 55.

The section of Soulard to the south of Geyer Ave was once part of the Crystal Spring Farm, owned by William Russell and his son in law, Thomas Allen. Beginning in the early 1850s, they began to sell off and develop parcels of their land, and set aside a parcel for the Sts. Peter and Paul Catholic Church. Knowing that St. Louis had been experiencing an influx of German immigrants, this was done as a business move, which made the surrounding area more desirable to the immigrants. Between 1855 and 1875, Soulard had grown into a densely populated urban neighborhood.

The furthest south portion of the neighborhood was laid out as a suburb of St. Louis known as St. George in 1836, by the city’s first mayor, William Carr Lane. It was located near the St. Louis Arsenal, and only saw minimal development until the 1870s. Due to the caves in this area, many of the breweries in 19th century St. Louis were located there, including Anheuser Busch. Wealthy St. Louisans, especially beer barons constructed homes in the hills of this part of Soulard in the 1850s through the 1890s, gradually filling in the southernmost part of the neighborhood.

Soulard was hit by the tornado of 1896, which caused millions of dollars of damage, and cost the lives of many in the neighborhood. The severe damage destroyed the Soulard Market’s original building, along with numerous other structures in Soulard, and many structures had to be rebuilt in its aftermath. Despite the damage caused by the tornado, many of Soulard’s oldest buildings still stand in the neighborhood.

Originally, the numbered streets in Soulard had names. South Broadway was Carondelet Ave, South 7th Street was South Market, although this was changed by the 1850s, South 8th Street was Fulton, South 9th was Decatur, South 10th was Buel, Menard Street is one of the only original street names, South 11th was Rosatti, South 12th Street was Hamtramck in the north and State in the south, South 13th was Closey in the north and Summer in the south, and Second Carondelet in the far south. Lafayette Ave and Soulard Street were also switched in the early 20th century, along with the renaming of all the streets to their current numbers in 1884, as part of an effort to make the street grid and addresses more continuous. In 1867, the current address numbering system was adopted to make the address numbers consistent across the whole city street grid. Before 1867, street addresses varied in number, and were not consistent in the same block. When researching old homes in Soulard, many times the address has been changed multiple times.

In 1947, Soulard was recommended for wholesale demolition by the Comprehensive Plan of 1947, which was written up by the city planner, Harland Bartholomew. Part of the neighborhood was cleared for the construction of highway 55, but thanks to historic preservation efforts, Soulard was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, and ultimately it was saved from the wrecking ball. Today, Soulard is one of the city’s most popular destinations, and it is home to the second largest Mardi Gras parade in the US.

St. Louis Place

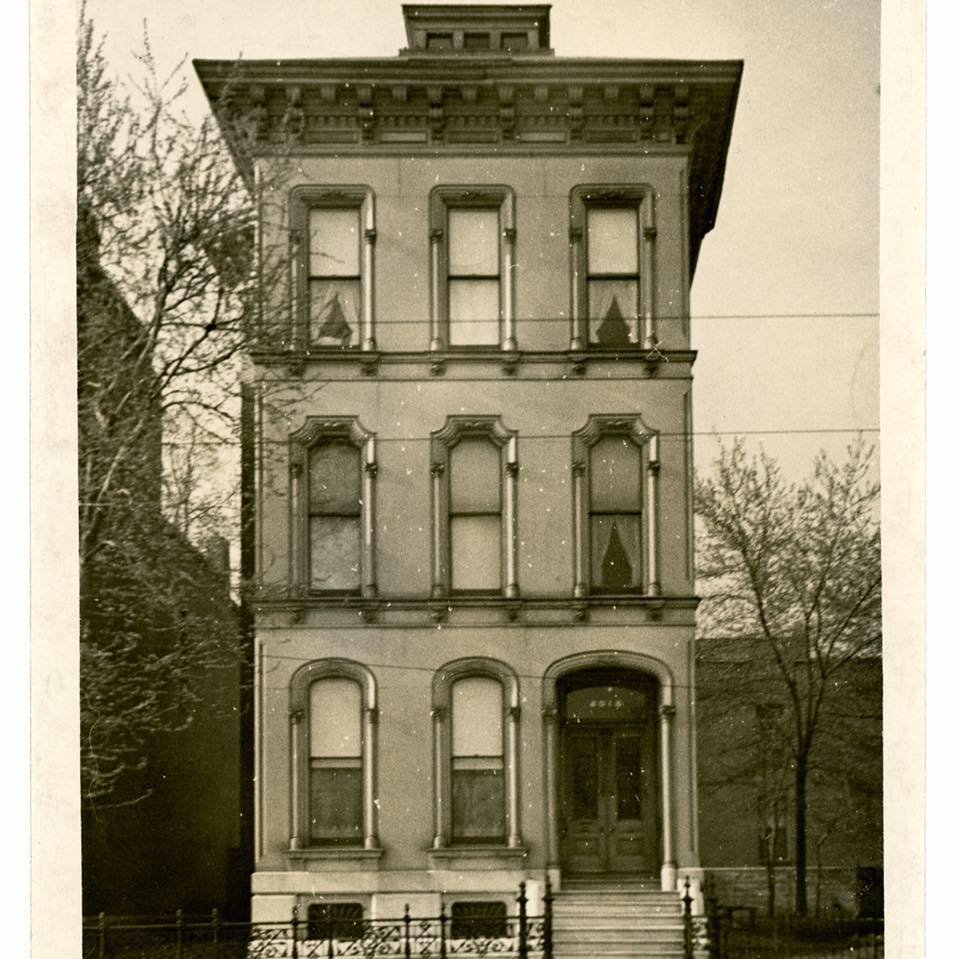

St. Louis Place is one of the older neighborhoods in North St. Louis, having been first developed in the late 1850s. The park after which the area is named is the third oldest park in St. Louis, and dates to 1850. The neighborhood is home to two historic churches, St. Liborius and Zion Lutheran, as well as the Columbia Brewery, which was founded in 1892, and became a Falstaff Brewery in 1948, before being converted to apartments. The neighborhood is also home to Millionaires Row, a section of St. Louis Avenue that was developed between 1870 and 1900, featuring some of the most opulent mansions in north St. Louis. During the 1950s and 1960s, the area suffered because of redlining practices, and suburban flight, and throughout the late 20th century, many of the historic buildings in the neighborhood were lost as the neighborhood continued to suffer from neglect. However, many buildings still survived, with Millionaires Row still standing as a testament to the historical and architectural significance of this neighborhood.

Laid out in 1870, Vandeventer Place became the prime location for the wealthiest St. Louisans to build their mansions. Vandeventer Place was not the first private street in St. Louis, but it was the most prestigious of them all in the late 19th century. Before the Civil War, Lucas Place, which was laid out in 1851, became the first private street in the city. It was the first attempt by wealthy St. Louisans to build a community at the edge of the city’s developed area to escape the industry and disease which were commonly associated with city living, especially in the years following the 1849 cholera epidemic. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, numerous large mansions had been built on Lucas Place, which was still being built on until 1876. At the time of the 1875 Compton and Dry map publication, Vandeventer Place was located in a remote part of the city, and only had two mansions built, while Lucas Place had been fully developed, and was still the most prestigious place to live in St. Louis. However, as industry began to encroach on Lucas Place, and its 30 year deed restrictions began to expire, Vandeventer Place surpassed it as wealthy St. Louisans began to move further west to the Midtown neighborhood.

Vandeventer Place was a private street which was developed with the funding from wealthy businessmen, Napoleon Mulliken and Charles H. Peck, who served as two of the neighborhood’s trustees. They bought the land from the estate of Peter L. Vandeventer, who was a prominent landowner in the area and had died in 1863. Peck and Mulliken bought lots across the street from each other and built the first houses on the new private street in 1871. To design the street’s layout, they hired Julius Pitzman, who became known as one of the most influential surveyors and private street designers in St. Louis history. A signature feature of Pitzman’s private street designs were the curvilinear streets and wide grassy boulevards that went down the middle of the street. Each side of the street was lined with lavish mansions and grand yards. Vandeventer Place also had fountains placed at the ends of the boulevard. While many mansions at the time were built on the main thoroughfares, the mansions of Vandeventer Place were secluded on a gated street, which was only accessible to the residents and their guests. The large gates which can be seen in Forest Park today were built on each end of Vandeventer Place in 1894.

Private streets allowed residents to control who could live on the street and what could be built , at a time when zoning laws and neighborhood associations were basically nonexistent. Deed restrictions placed on the lots required buildings to have a setback and a minimum cost of construction and size of the house. Residents all paid into a neighborhood association who privately maintained the infrastructure on the street, independently from the city. Many of the features of private streets laid the foundations for later suburban developments, such as homeowners associations, cul de sacs, and gated communities. While Vandeventer Place no longer exists, St. Louis has several other private streets which still remain today.

By the late 1890s, Vandeventer Place began to decline, with the last mansion constructed on the street in 1898. Mansions in the Central West End became more desirable than Midtown, which began to face the same issues as Lucas Place before it. The industries and crowded conditions of downtown began to reach the midtown area, and the wealthiest residents of Vandeventer Place began to start moving to Portland and Westmoreland Places in the early 1900s and 1910s. At first, the extremely wealthy captains of industry began to be replaced by less prominent, although still wealthy individuals, like doctors and lawyers. They maintained the exclusivity of the street through the first two decades of the 20th century, as some of the wealthiest residents were still living there at this time, and fought hard to maintain the prestige of the street. However, by the 1920s, the surrounding area in Midtown along Grand Avenue became home to the theater district which drew thousands of St. Louisans to the area via streetcars and automobiles, which brought noise and smoke to the area, and further pushed many of the wealthy residents west. The area really began to decline after the Great Depression, as property values diminished while the mansions remained expensive to maintain. Some of the mansions were turned into boarding houses, against the original charter of the private street, while others, such as the Mulliken mansion, David R. Francis mansion, and Pierce mansion were razed. The end came after World War II when in 1947, the government bought the eastern half of the street and razed the mansions in 1950 to make way for the VA hospital. Then, in 1959, the western half was razed for the juvenile detention center.

Other North St. Louis Neighborhoods

There are a number of historic neighborhoods in the northern part of St. Louis with rich history that have not been covered in detail yet on this page, such as Jeff Vanderlou, College Hill, and the West End. Here is where the articles on these neighborhoods are posted.

Other South St. Louis Neighborhoods

South St. Louis has a number of historic neighborhoods which have not yet been covered in detail on this page, including Compton Heights, Fox Park, and Dutchtown. Here is where articles on these neighborhoods are located.